great mosque of córdoba

arch403 - mediterranean cities, fall 2016córdoba, es

prof. heather grossman

context

![]()

the great mosque of córdoba, located in córdoba in southern spain, has had many names and uses throughout its lifetime. while it started out as a christian basilica, san vicente mártir, it then became the great mosque of córdoba, an islamic religious space. after many renovations and additions, the building eventually came under christian rule again, becoming la catedral de santa maría. today, though it technically belongs to no one, the building still functions as a christian basilica and a tourist destination. in addition, the building was renamed as “el conjunto monumental mezquita-catedral de córdoba” (“the combined monumental mosque-cathedral of córdoba”).

islamic

basilíca de san vicente mártir

there’s controversy regarding whether this church existed before abd al-rahman i came to córdoba. some academics believe that the archaeological evidence is not sufficient, but others believe that the archaeological evidence and written accounts show that the basilica did exist. if this basilica existed, the building was shared between christians and muslims from 755 to 785.

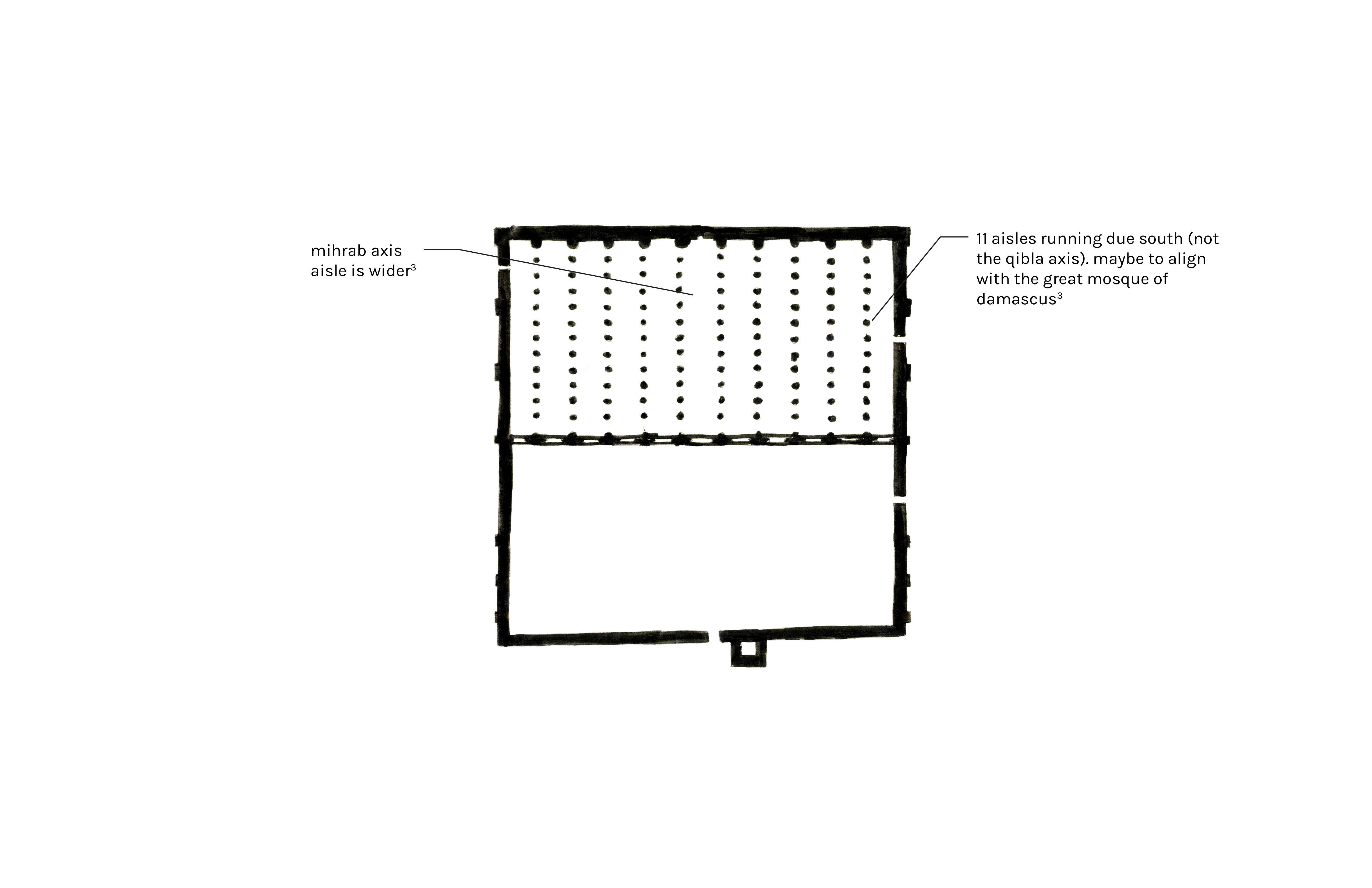

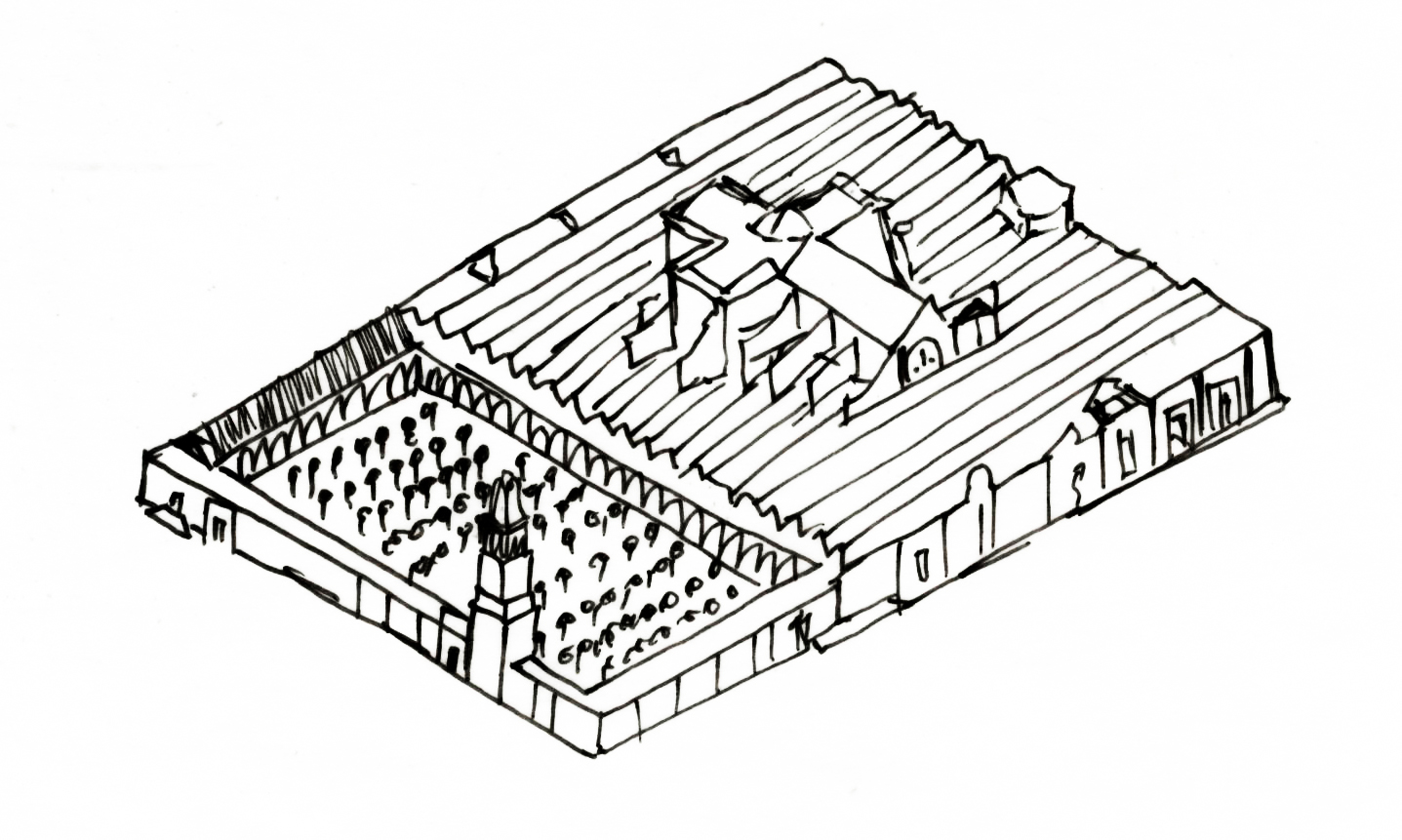

abd al-rahman i (785 demolished, 786/7 completed)

local arches

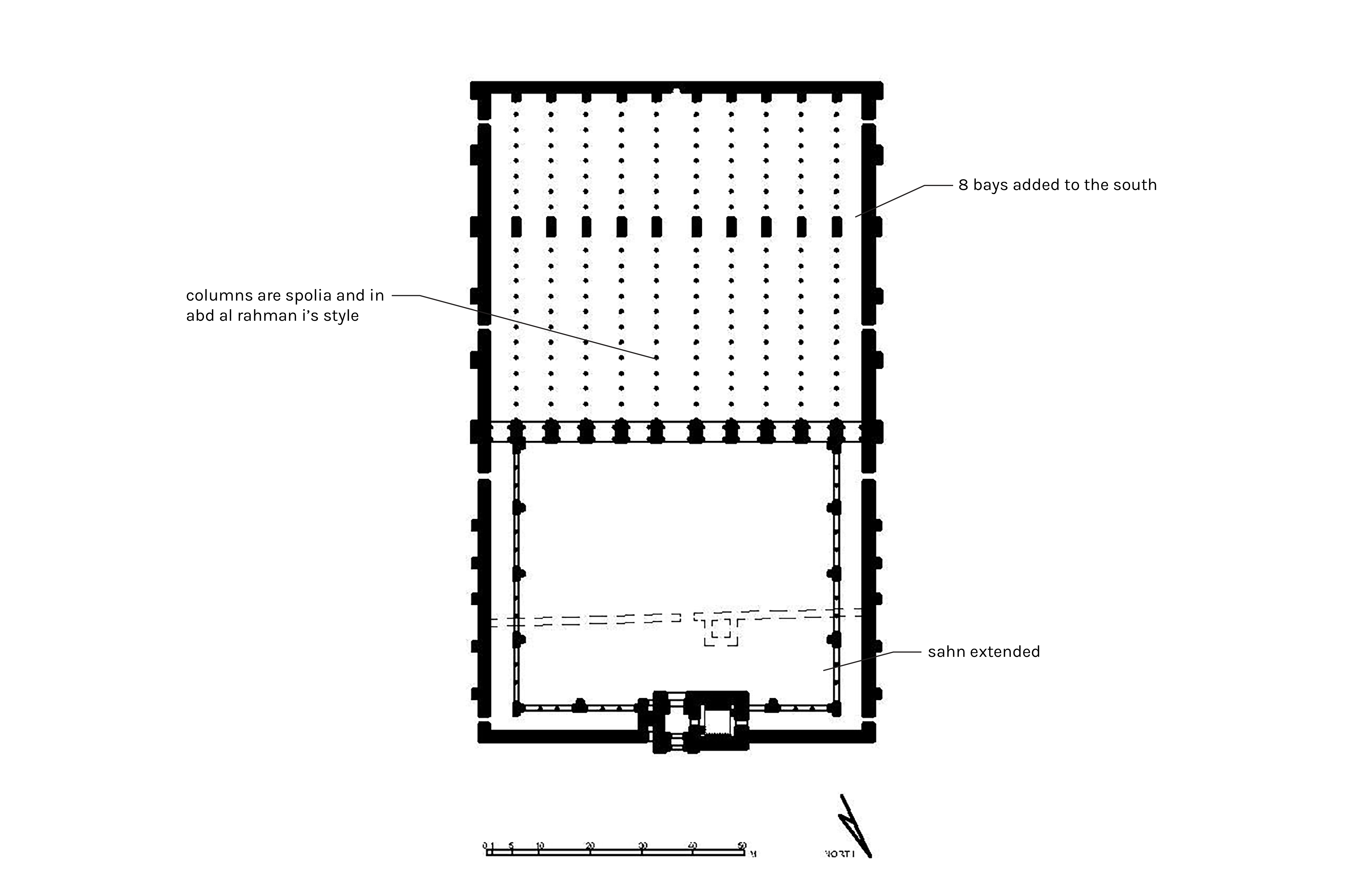

abd al-rahman ii (836 completed)

muhammad i (855/6 completed)

muhammad i (855/6 completed)

maqsura: covered area for the emir to pray in privacy. this image is of a later maqsura; muhammad’s was replaced during a later expansion.

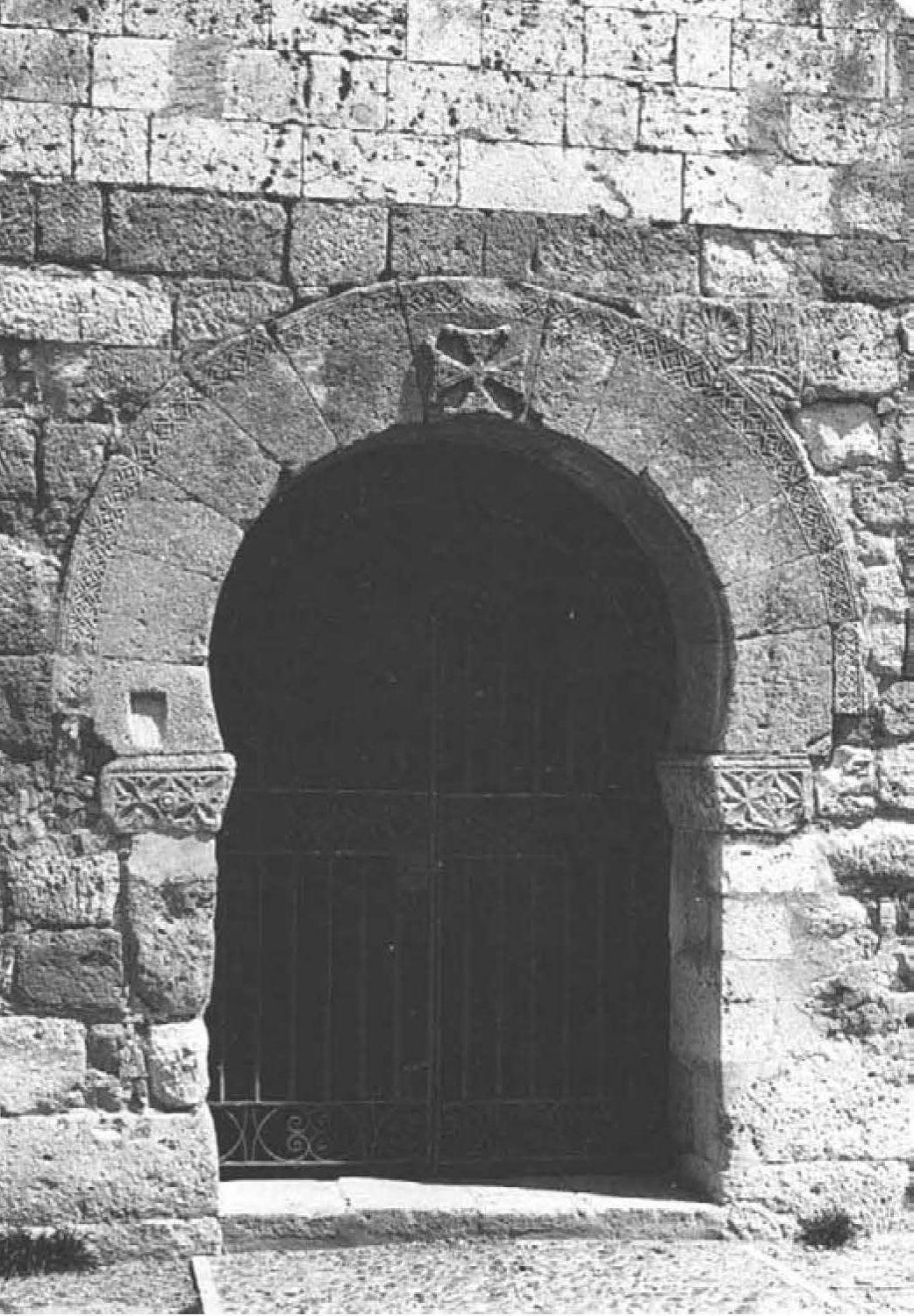

bab al-wuzara mimics the interior arches with its alternating false voussoirs. however, these are made of stucco and brick, more extravagant materials than the interior ones.

abdallah (r. 888-912)

abdallah added a sabat, a covered passage, from the maqsura to the palace so that, according to legend, he could go to pray without the congregation standing up every time. though this was supposed to be a pious action, it also isolated the emir.

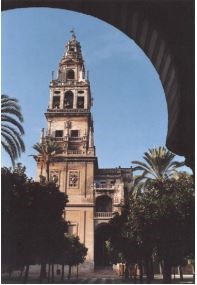

abd al-rahman iii (951 completed) 👑

abd al-rahman iii redid the sahn (courtyard) to reflect the interior through the use piers and columns. he also rebuilt the previous minaret with two staircases. as a symbol of islam, the tower competed with the bell towers of churches in córdoba.

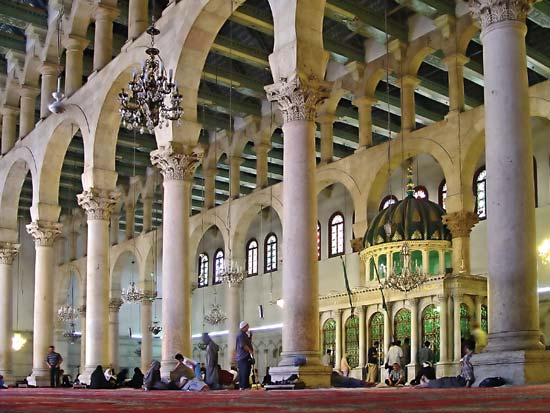

al hakim II (962 completed) 👑

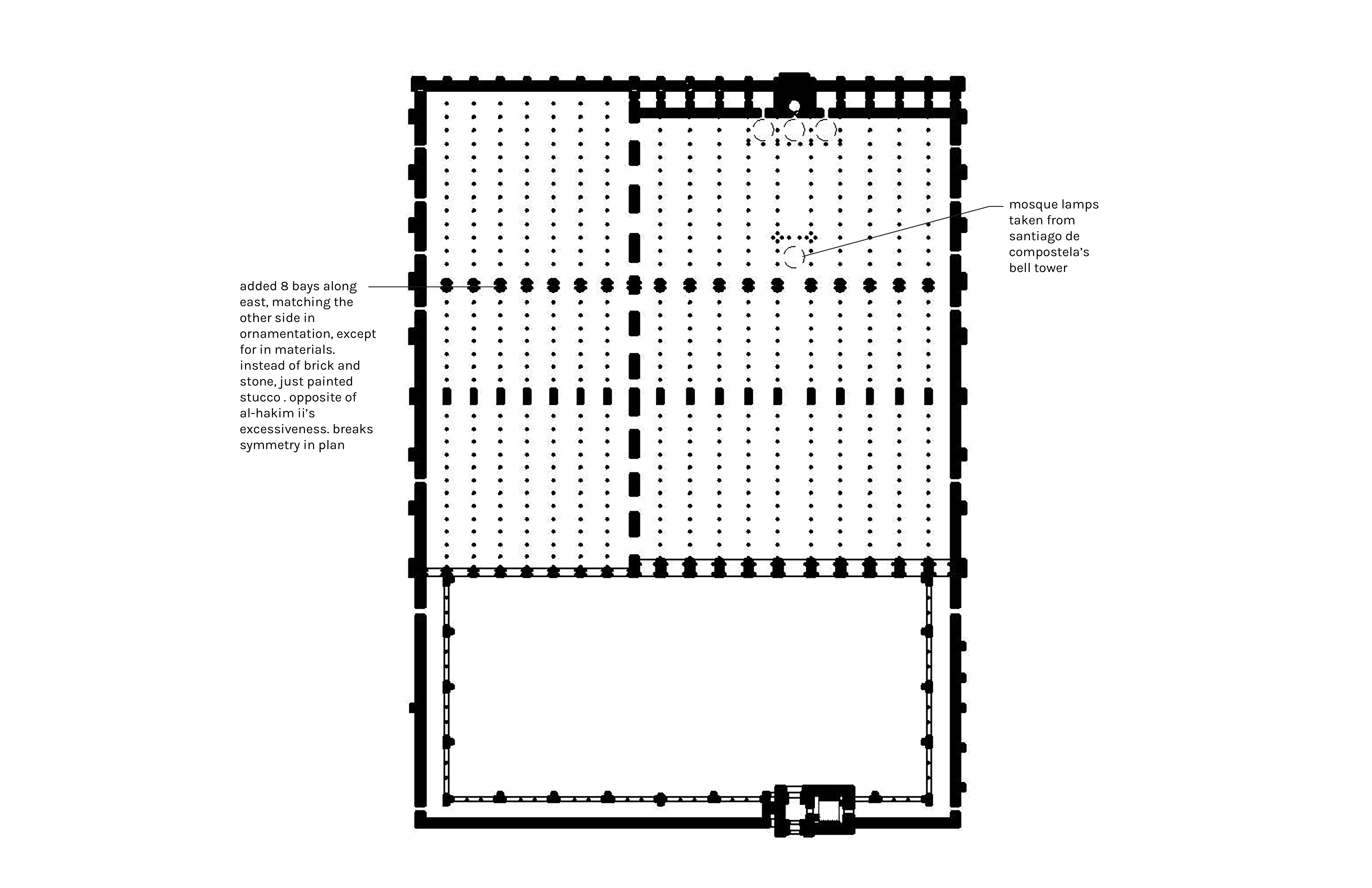

al-mansur (advisor) (987/8 completed)

christian

the fall of córdoba

on june 29th, 1236, córdoba fell to ferdinand iii. it was converted into a cathedral, la catedral de santa maría. ferdinand iii had a cross and royal banner added. he also returned the bells to santiago de compostela.

additions to the cathedral

when it was converted to a cathedral, ferdinand iii created a chapel, la capilla de villaviciosa, but kept the rest intact because he, and other conquerers, thought the mosque was beautiful.

renovations in the 13th century

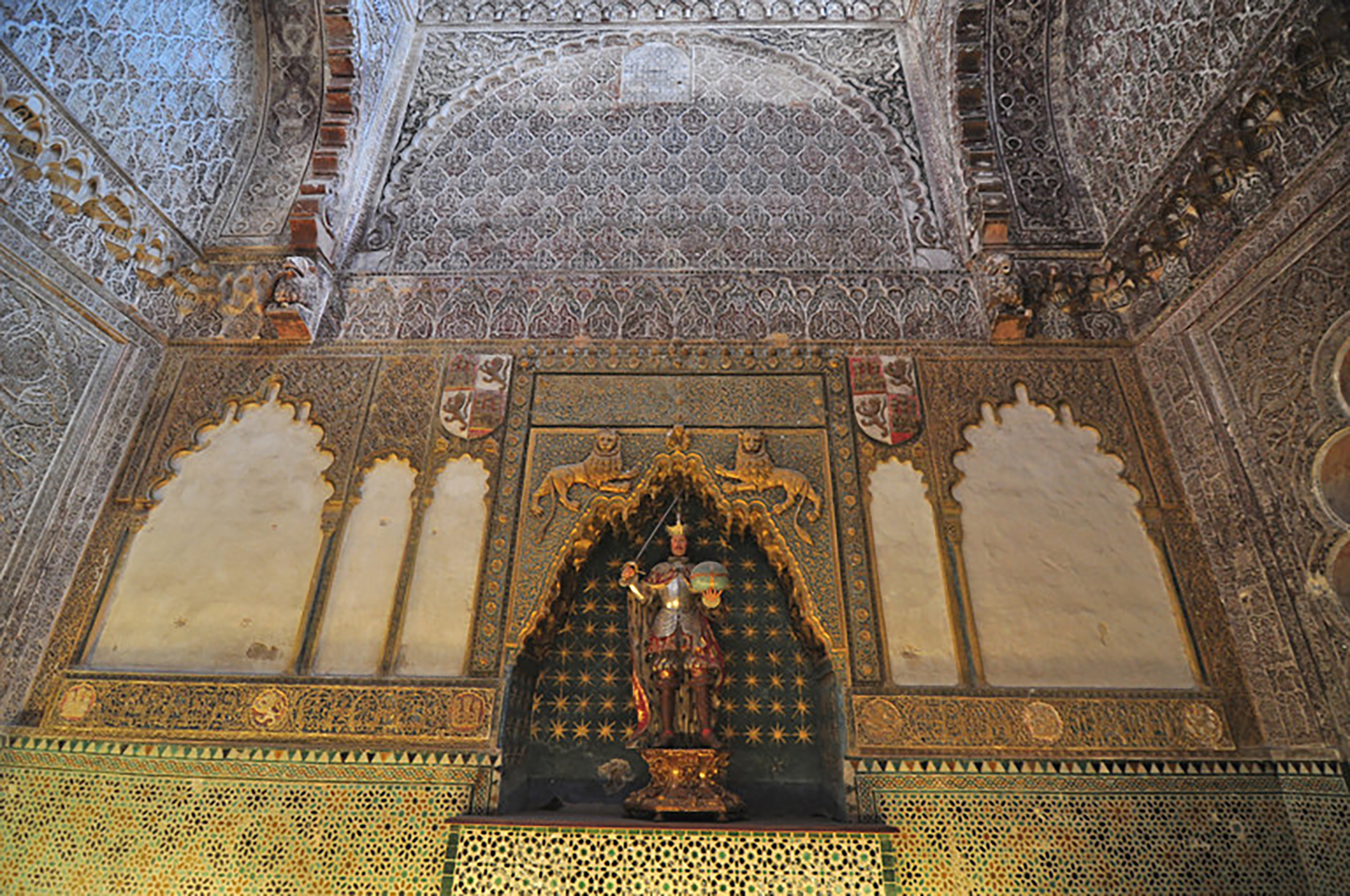

in the 13th century, the christians built this chapel inside the former mosque. It was in the mudejar style, had arabic inscriptions, and carved stucco, but functioned as a “pantheon for the kings of castille.” rather than destroying the mosque, the christians reappropriated it to show their power.

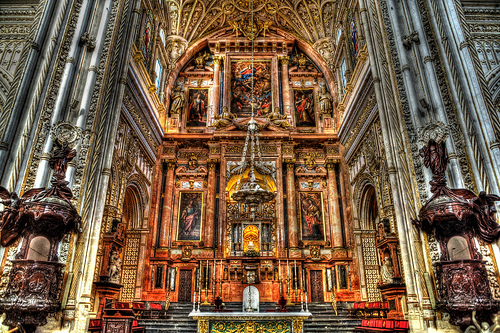

the largest project

in the 15th century, the clergy convinced charles v to allow them to build a cathedral in the center of the mosque, much to the chagrin of the townspeople. however, after charles v had seen the progress, he said, “you have taken something unique and turned it into something mundane.”

today

as of september 29th, 2016 unesco is allowing an access point in the mosque for processions during la semana santa but it involves breaking some lattice built in 1972.

as of march 31st, 2016 the new name of the building is “el conjunto monumental mezquita-catedral de córdoba” (aka. the combined monumental mosque-cathedral of córdoba)

on march 11th, 2016, the secretary of the municipality of córdoba said that the great mosque of córdoba does not belong to any person, organization or government.

sources:

dodds, jerrilynn d. “the great mosque of córdoba.” al-andalus: the art of islamic spain. ed. jerrilynn d. dodds. n.p.: n.p., n.d. 11-25. print.

kroesen, justin e.a. “from mosques to cathedrals: converting sacred space during the spanish reconquest.” mediaevistik, vol. 21, 2008, pp. 113–137.

limón, raúl, and paco puentes. “la unesco permite abrir un acceso en la mezquita para las procesiones.” el país. n.p., 29 sept. 2016. web. 05 dec. 2016.

lucas, ángeles. “el cabildo insta a resolver por vía jurídica la titularidad de la mezquita.” el país. n.p., 31 mar. 2016. web. 5 dec. 2016.

morán, carmen, and a. j. mora. “un informe municipal declara que la mezquita de córdoba no tiene dueño.” el país. n.p., 11 mar. 2016. web. 05 dec. 2016.

ruggles, d.f. “encyclopaedia of islam, three.” brill. brill reference online. web. 6 dec. 2016.