la alhambra - power and architecture

span228- spanish composition, spring 2016granada, es

prof. josé villalobos

When you think about Spain, you likely think about the Catholic king and queen, Ferdinand and Isabel. However, Spain has had influence from Islamic culture. There was a time when Islamic caliphates controlled the majority of the peninsula. This unified caliphate eventually broke into smaller kingdoms and in 1232, the Nasrid dynasty ruled the last bit of Muslim Spain -- Granada. The Nasrid sultan was forced to accomodate to the Catholic kings to the north and to the Muslim rulers in Morroco in order to maintain his power. In Granada, the sultan constructed a palace, la Alhambra, named after the Arabic word for “red.”1 Not only does this palace cement Islamic culture as a cornerstone of Andalusían culture, but it’s a salient example of how architectural design can create and shape power. Because the treatment of two of la Alhambra’s main spaces-- el Patio de Arrayanes and el Patio de los Leones--is different in both their parti and their ornamentation, they create different types of power.

patio de arrayanes

patio de arrayanes

The Patio de Arraynes (Patio of the Myrtles) is the most public patio of the palace while the Salón de Embajadores (Room of the Ambassadors) was used for state functions.

These spaces are arranged in a longitudinal plan. The patio is a rectangular space that is connected to a square room to the north. There is only one public entrance into the Salón de Embajadores, to the south. The water extends through the center of the patio in order to extend the distance guests must walk in order to reach the Salón de Embajadores. The sultan negotiated with the Catholic kings and Morrocan rulers in this room. The circulation path in this public area was controlled by the sultan -- indicating that the sultan could control these foreign dignitaries in his palace.

Another means for control was the rectangular room between the Patio de Arraynes and the Salón de Embajadores. This room was very similar to a palace in Syria. There, this room functioned like a waiting room and as a place to protect the caliph from attack. In la Alhambra, it holds an identical role and serves to indicate to the visitors that the caliph does not find them trustworthy. This control and scepticism of guests through architecture are demonstrations of the political power of the caliph.

Another means for control was the rectangular room between the Patio de Arraynes and the Salón de Embajadores. This room was very similar to a palace in Syria. There, this room functioned like a waiting room and as a place to protect the caliph from attack. In la Alhambra, it holds an identical role and serves to indicate to the visitors that the caliph does not find them trustworthy. This control and scepticism of guests through architecture are demonstrations of the political power of the caliph.

In contrast, the centralized plan of

el Patio de los Leones (Patio of the Lions), de la Sala

de Dos Hermanas (Room of Two Sisters) y de

la Sala de los Abencerrajes (Room of the

Abencerrajes), indicates a more personal level of power. These spaces were used as familial spaces. The sultan, his wives, and the rest of the family lived in this area.3 This patio is almost the same size as the Patio de Arrayanes but is arranged in a centralized parti. This garden has four channels of water that meet at the fountain in the center. This type of plan is called a chahar bagh and is a popular Islamic garden plan4

. The channels seem to be the same size on both axes, but they aren’t. The north-south axis’ channels extend further, than the east-west axis’.

These channels make the long side of the patio -- the east-west axis -- seem siginificantly smaller, centralizing the patio. This visual effect helps to equalize the patio -- the longer axis has shorter channels and the shorter axis has longer channels. The patio also has many entrances and unclear walking paths. The Sala de Dos Hermanas and the Sala de los Abencerrajes both have centralized floor plans. They’re both square with a fountain in the center of the room that marks the end of the channels from the center of the Patio de los Leones. These rooms suggest where the sultan’s family should look while in the space but they don’t restrict where they can walk. The equalization of the patio and the symmetry of the two connected rooms illustrate the patriarchal power of the sultan. This type of power is more covert and restrained, but is still present. Restricting the sultan’s family’s movement within their private space would be inconvient, but the design of the space still shapes the family’s experience. Thus, in contrast with the restricted circulation of visitors in the Patio de Arrayanes, the architecture of the palace gives the family freedom of movement.

These channels make the long side of the patio -- the east-west axis -- seem siginificantly smaller, centralizing the patio. This visual effect helps to equalize the patio -- the longer axis has shorter channels and the shorter axis has longer channels. The patio also has many entrances and unclear walking paths. The Sala de Dos Hermanas and the Sala de los Abencerrajes both have centralized floor plans. They’re both square with a fountain in the center of the room that marks the end of the channels from the center of the Patio de los Leones. These rooms suggest where the sultan’s family should look while in the space but they don’t restrict where they can walk. The equalization of the patio and the symmetry of the two connected rooms illustrate the patriarchal power of the sultan. This type of power is more covert and restrained, but is still present. Restricting the sultan’s family’s movement within their private space would be inconvient, but the design of the space still shapes the family’s experience. Thus, in contrast with the restricted circulation of visitors in the Patio de Arrayanes, the architecture of the palace gives the family freedom of movement.

patio de los leones

patio de los leonesThe clarity and simplicity of the ornamentation of the Patio de Arrayanes and Salón de Emabajadores also help to give the sultan political power. The Patio de Arrayanes has a rectangular bed of wtaer that ends in two small circular fountains. These simple forms are similar to a normal house. The arches (fig. 2) to the north are also similar to arches that appear in noble houses5. Instead of the traditional five arches, there are seven here. This humanizes the sultan while simultaneously illustrating that he is better than the nobles. In Islamic architecture, an entry with water illustrates the power of the patron of the building because water is a rare and precious resource in many Islamic areas6. Here, there is an aboundance of water and fountains that celebrate it in the entrance to the political patio. However, the restrained ornamentation celebrates it in a non-ostentatious way. In the same way the arches do, this humanizes the sultan while reminding visiting dignitaries that he holds the power.

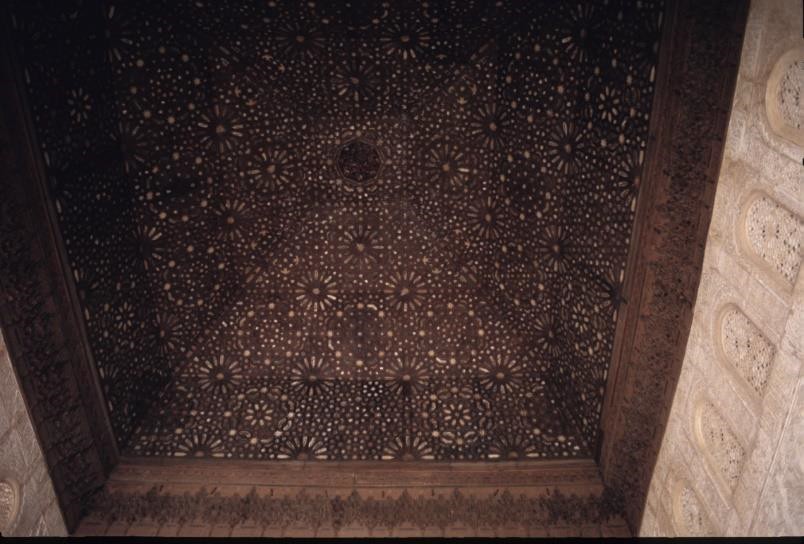

In the Salón de Embajadores, the ornamenation is reserved but clear. The ceiling is made of wood (1) and it is quite simple, especially in comparison with the ceilings on the other side of the palace. Additionally, there is a quote from the Quran that overtly proclaims the power of the sultan -- “Blessed is he in whose hand is the kingdom”7. The ornamentation of the patio and rooms are so obvious because the visitors are only there for a short time. These blatant displays of power are necessary to ensure that visitors understand their position while present. The combination of ornamentation that gives the sultan power and humanizes him is politically motivated becuase the image of a benevolent ruler is important for a leader.

(1) wooden ceiling, salón de embajadores

(1) wooden ceiling, salón de embajadores

(2) muqarnas, salón de dos hermanas

The Patio de los Leones, the Sala de Dos Hermanas, and the Sala de los Abencerrajes illustrate the message of patriarchal power through complex ornamentation. In the Patio de los Leones, there is a fountain that celebrates the entrance of water, similarly to in the other patio. Here, however, there are twelve lions surrouding the fountian. These symbolize the power and the benediction of the sultan through a metaphor with King Solomon, a religious figure who was known for being a good king8. The lions and their significance are complex but are concrete--literally and culturally. This helps to solidify the message that the sultan is a good ruler. Inscriptions in the Salón de Dos Hermanas, while not quaranic, are another way for the sultan to illustrate patriarchal power. This inscription, a poem written from the perspective of a garden, has images of constellations like Pleiades, Orion, and the moon9. These images connect with the ceilings in the two rooms. Both the Salón de Dos Hermanas and the Salón de Abencerrajes have ceilings made of muqarnas (Fig. 5). Muqarnas are very complex -- each piece is handmade and looks like a beehive. The poetry helps turn this beehive-looking structure into a metaphor for the cosmos10. This is important because it is a more educated and complex symbol than the one that is experienced in the Patio de Arrayanes and the Salón de Embajadores. Because the family lives in the palace and sees these symbols every day, the message can be more complex. Every day the family lives here, they see and can think about the symbols and messages within the architecture and know that the sultan is powerful. The ornamentation is a symbol of patriarchal power because in the context of the Patio de los Leones the nearby rooms, the sultan is a father and a husband.

The Alhambra is a palace that demonstrates how the function of a building informs the form through metaphors and messages. In the Patio de Arrayanes and the Salón de Embajadores, this message was one of political power, informed by the political function of the space. In contrast, in the Patio de los Leones, the Sala de Dos Hermanas and the Sala de Abencerrajes, the message of power was patriarchal because the function was a living space. Using the plan and ornamentation, two facets of form, the sultan and his architect created a palace that illustrated vital messages in its social structure.

Sources

1 D. F. Ruggles, Encountering Islamic Architecture (Urbana-Champaign: Universidad de Illinois Urbana-Champaign 2016), Capítulo 9.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 D. F. Ruggles, “Granada and the Alhambra” (presentación de Islamic Gardens and Architecture, Urbana- Champaign, 25 febrero, 2016).

8 Ibid.

9 Ruggles, Encountering Islamic, Capítulo 9.

10 Ibid.